Natural and Syntheticus

The etymology of the word synthetic derives from the Greek sunthetikos, the Latin syntheticus, and the French synthétique, which all in some form translate simply as, to 'place together'.

In the 1950s synthetic fibres became popular in the textiles industry when Polyester joined Nylon and Rayon developed earlier in the 20th century. Mid-century modernist patterns printed on these fabrics became associated with a new post-war optimism, but also an age of mass-produced culture, and the word synthetic has since often been synonymous with something cheaper and less authentic than the ‘real thing’.

In music in 1964, Robert Moog developed the first commercially available Moog synthesizer, soon adopted by experimental musicians of electric or electronic music. The Italian musician Giorgio Moroder was one of the first innovators in this field and since the late 60s Moroder has composed and produced electronic synthesizer-based music with so many artists, he is sometimes referred to as the 'father of disco'. Nevertheless, synthesizer or ‘synthetic’ music can also at times carry associations of kitsch, fairground attractions, repetitive disco beats – or music which is considered less sophisticated than that produced by a ‘classical’ keyboard.

In art, there is also a common misconception that natural earth pigments, are dug out of the ground, extracted like root vegetables, and turned into paint while still fresh in artisanal workshops, whilst synthetic pigments are cheaper manufactured iterations conjured in labs from inferior Jello-like ingredients.

Whilst it’s true that the prehistoric palette included many naturally occurring red and yellow ochre clay pigments still used to this day, synthetic pigments have also been produced since times of antiquity when Egyptian Blue was first made by placing together a mixture of silica, lime, copper, and an alkaline, to produce the blue known to the Romans as caeruleum.

The Greeks and Romans also made Verdigris by corroding copper with Vinegar and in pre-Columbian Mesoamerica, Maya blue was made by the Mayans and Aztecs by bringing indigo dyes into contact with natural clays to create an extremely permanent vibrant blue. In the Middle Ages the practice of ‘alchemy’ produced new colorants employed in Medieval manuscripts, and in the early 18th century, Prussian Blue was the first modern synthetic pigment discovered by the age-old method of chance, when this was discovered by accident. A brighter and more stable French Ultramarine was later created in 1828 as a synthetic alternative to Lapis Lazuli, and in 1856 at the age of 18, the Victorian chemist Henry Perkin discovered Mauveine—the first commercialized synthetic dye discovered whilst searching for a synthetic form of quinine to treat malaria, when he too accidently conjured a black precipitate and noticed a violet substance later named as Mauveine.

A new era in the chemical industry was born. Not only was Mauveine cheaper and easier to produce than conventional purple dyes such as Tyrian purple — made from small molluscs — but other synthetic dyes and lake pigments would follow revolutionising fashion, artists' palettes and the way pigments were sourced. New shades of red, yellow, green, and blue following purple. Scientists began using dyes to observe cells under microscopes, revealing never before seen images of life’s mysteries; and it is this research into synthetic dyes with its many ramifications that underpins modern organic chemistry and methods of colour ‘synthesis’ today.

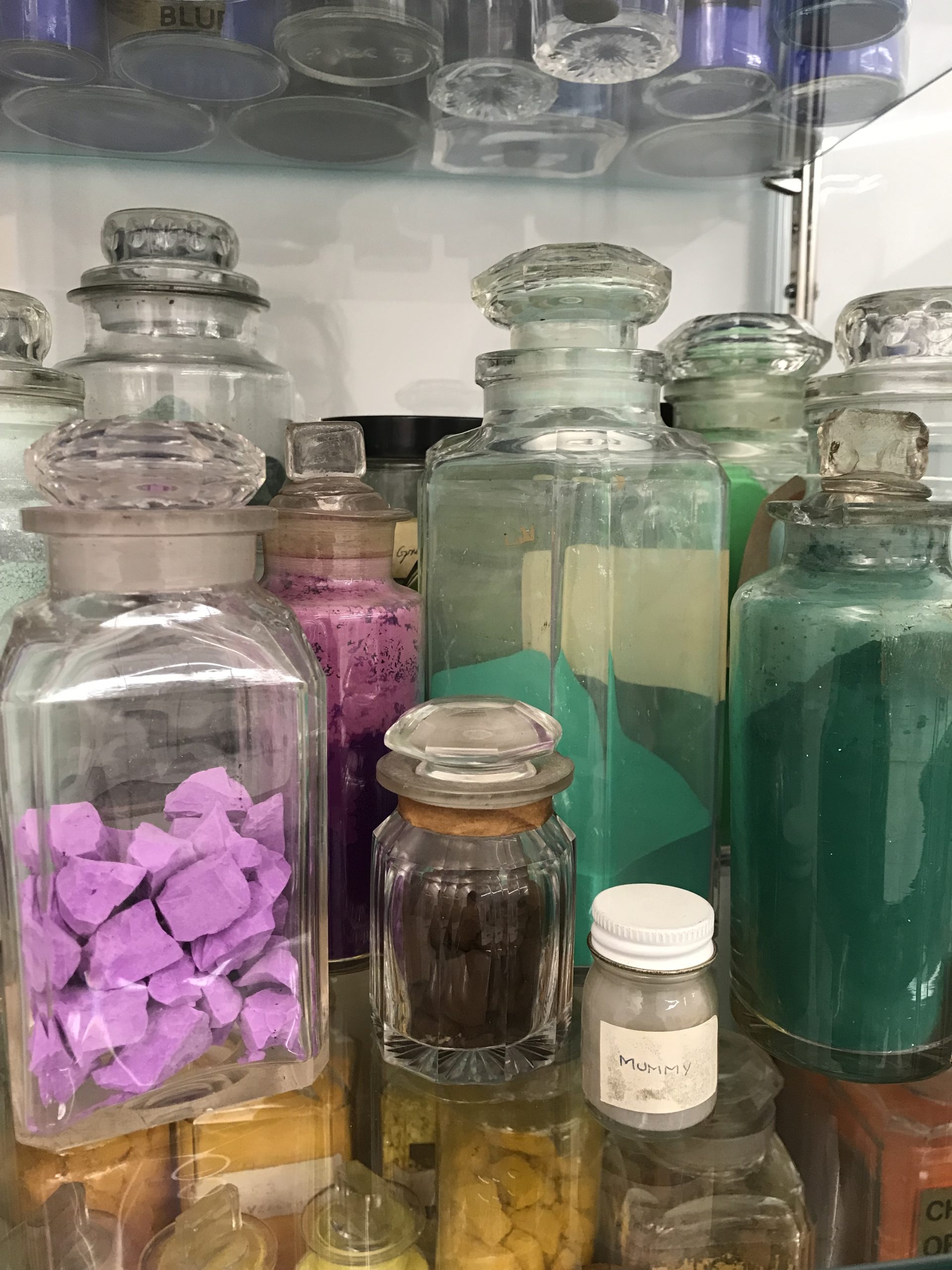

Synthetic pigments offer advantages extending beyond ease of production and lower manufacturing costs. They are often more stable than their former predecessors (such as Permanent Alizarin Crimson), they have replaced previous methods involving hazardous materials (such as Vermilion made by heating mercury with sulphur), or unethical practices (such as the gory Mummy Brown made by grinding segments of an Egyptian mummy and mixing with asphalt).

Pigments are inextricable tied to our history and evolution. They tell our story indexically pointing to advances artistic and scientific. Despite the many advantages synthetic pigments offer, such is the mythology of pigments that modern synthetic equivalents – Hansa and Azo Yellow, Pyrrole Red, Quinacridone Violet, Phthalocyanine Blue and Green to name a few – sometimes have a hard job competing with names such as Naples Yellow, Burnt Umber or Burnt Sienna; Naples, Umbria and Sienna names which from the outset conjure romantic images of Italy and Mediterranean soil and light. According to some theories Sienna is the original setting for a short story by Masuccio Salernitano (1410–1475) – Mariotto and Ganozza, later adapted by Luigi da Porto (1485–1529) as Giulietta e Romeo – which in turn served as the basis for William Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet (which Shakespeare set in Verona not Sienna). Hansa and Azo on the other hand owe their etymology to the scientific language and terminology associated with their making – azo coupling the term in organic chemistry used to produce Azo Yellow – and much like new planets discovered – myths of Venus and Saturn have been times replaced by a more pragmatic language reflecting a more scientific era; such as for example, WASP-121, also known as CD-38 3220, a recently discovered large exoplanet outside the Solar System; 855 light years away and as big as the sun.

Mythology and etymology aside, earth pigments such as Burnt Sienna (made by heating Raw Sienna) are becoming scarce due to the gradual depletion of natural deposits, making it increasingly challenging to obtain in their original or natural form. Today, many manufacturers opt to produce a synthetic Burnt Sienna, but somehow the number PR101 relating to this synthetic iron oxide, doesn’t have the same ring. Here perhaps the famous adage, "A rose by any other name would smell as sweet", might apply not to smell, sweet aromas, or music, but to new colours once plucked from nature now synthesised.