Drawing Blood by Bethany Husband

In February of 2020 I visited the Head and Neck department of Charing Cross Hospital for a week to observe and draw surgery. I was frequently asked by those around me “what are you doing here?” Despite the lengthy process I had been through to access the surgical theater, I was stumped by this question. When arranging my entry,

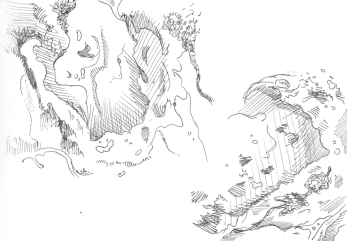

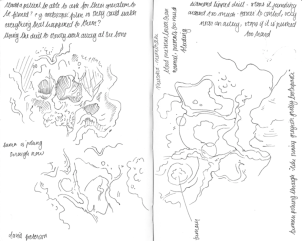

I said that I wanted to observe and draw surgery, particularly focusing on how the body is compartmentalised.

I was intrigued by how surgical drapes are used to conceal all but the section of the body to be operated on. I was also interested in the legacy of drawing surgery. How can drawing be an investigative method to better understand the surgical process? What is the historical link between artist and surgeon, particularly in Rembrandt’s seminal painting, The Anatomy Lesson of Dr Tulp?

Despite these initial points of entry, I thought I could cast off these predispositions and enter the space as a neutral, objective observer. This way I would let the process shape me, rather than imposing my own assumptions onto the operating theatre.

I soon learnt that there is no such thing as a passive observer. There is always an element of voyeurism to these processes and my decision of what should be drawn was marked by my subjectivity. Alongside my attempt at neutrality, I considered the assumption of medical and scientific objectivity. Geneticist, Barbara McClintock, wrote about the problem of masculine objectivity in science, showing how this attempt at clinical neutrality is intrinsically flawed. Knowledge is always situated in a specific historical, social context, predicated on the experience of the individual or specific demographic. Western medicine, as McClintock points out, is the legacy of the white male. As a result, notions of objectivity must be questioned. In both Rembradnt’s painting and the surgical practices we see today, there is a sense of the advancement of the singular medical gaze, assumed to be universal but truly played on a very limited understanding of the body.

Yet I had attempted neutrality. In the operating theatre, when asked what I was doing there, I tried to keep my answers vague. I wanted to draw surgery, understand the process. Surgeons, anaesthetists and matrons would peer over my sketchbook and comment on what I had chosen to record, as if this might reveal my purpose there. I also shared this notion; that my drawings might point towards the result of intersecting medical and artistic knowledges. I came to understand that there is indeed a rich history of this intersection.

This is present in Rembrandt’s painting, with the closeness between the artist and surgeon's hand. As Dr Tulp draws blood, Rembrandt draws blood. Tulp’s hand rests on the forceps in the same way Rembrandt would cradle his brush. Tulp opens the body, exposing the anatomy within, and Rembrandt immortalises this action, opening the body’s mysteries to all who view the painting. Throughout history, artists have played a crucial role in recording and diagramming the anatomy exposed by surgeons. Eli Heckscher references the prominence of the artist in the development of anatomical teaching as they represent the “surface anatomy of the body so admirably in their free creations that a work of art could at times inspire medical scholars as much as the nature itself.”

If we take this historical closeness between medical and artistic development, we can also draw a line between the misconception of objectivity in both cases. I find that art is never merely neutral documentation and there is no such thing as a truly objective medical gaze. My choice of subject speaks to this curious intersection of knowledge between the medical and artistic in the operating theatre. This was something that seemed novel to me at the time, but in reality we can see a rich history at play. So, when asked again, “what are you doing here,” perhaps “drawing surgery” might suffice as a response.