BEAUTY MATTERS

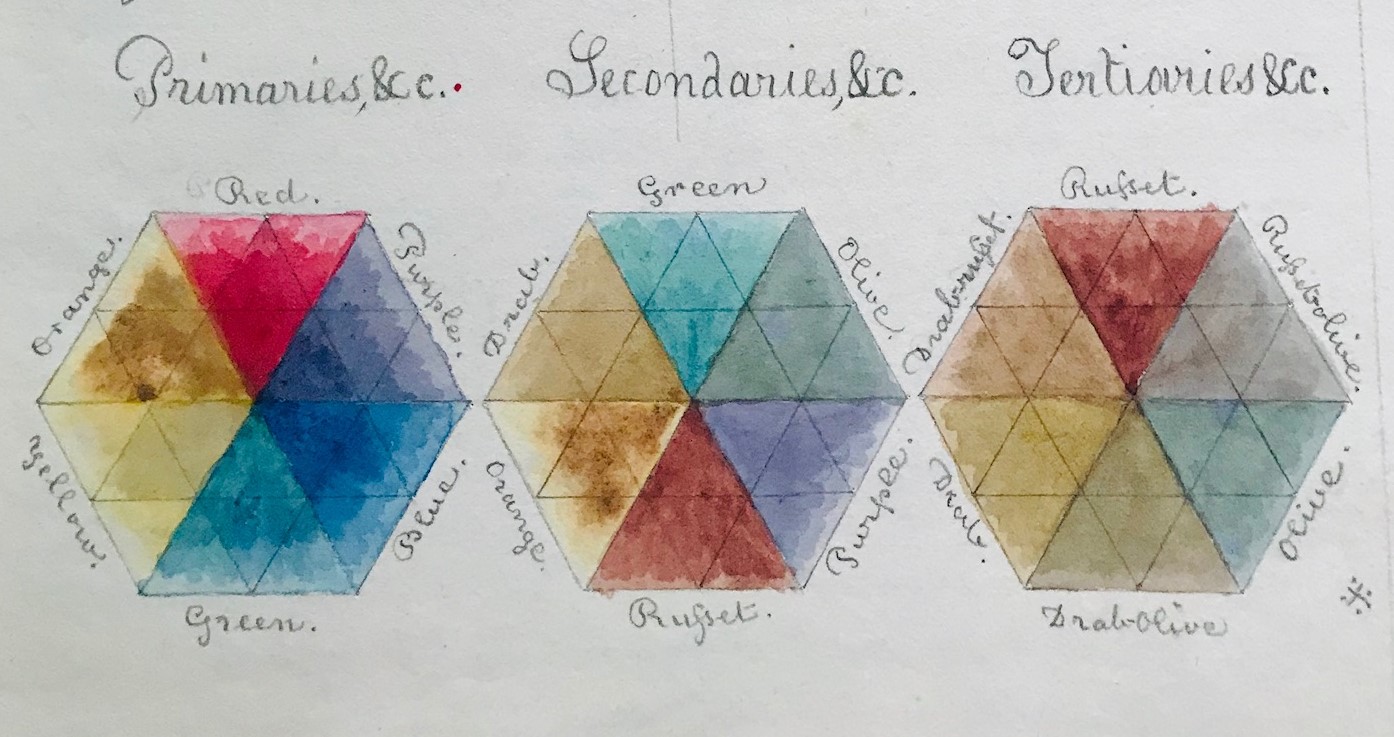

*(Image: George Field)

By Alastair Gordon | Dec 2020

We have heard it said beauty is in the eye of the beholder.

In the past, beauty has been associated with the unquenchable virtues of goodness and truth. In a classical sense, beauty involved a harmonious assembly of shapes and forms. In the Dionysian tradition, it was more about lavish abandonment and the glorious negation of rules. Today, we might even think of beauty as a social construct or human invention. Something to describe the finer things in life, a fancy dinner, an opulent painting or even a conduit of power. Some might associate beauty with the cynical sides of advertising agencies and the commercial art world. In such a medley of meaning, is it possible to characterise beauty in a conclusive sense?

What can be said in defence of beauty? Does it even matter for artists today?

One reason we find it difficult to talk about beauty is its changing characterisation through the years. Greek philosophers Plato and Aristotle described a formal beauty of harmonious relations experienced through nature, evidenced between musical notes, ratios of numbers and the more noble dimensions of architecture. They riffed to the legacy of Pythagoras who described, “all things being formed in accordance with harmony”. Pythagoras identified such harmony of form in the natural world, in the stars and, therefore, amongst the gods. As such, from these early descriptions of beauty, there was a symbiotic relationship between beauty and her ancient sisters, goodness and truth.

We live a long way downstream from a time when beauty, goodness and truth were assumed as inseparable. Even still, many of us still consider beauty to be something good and perhaps true even if we can’t agree on what these things actually look like.

Oscar Wilde believed strongly that art didn’t have to express anything beyond itself. To put it another way, art for art’s sake. While this mantra is often attributed to Wilde, it doesn’t actually appear in his writing. However, he notoriously claimed in the preface to his dark novel The Picture of Dorian Gray, “All art is quite useless.” When art becomes immoral or amoral, it no longer bears a responsibility to goodness and truth. Indeed, beauty becomes its own justification. This way of thinking about beauty has had such a penetrating and popular effect on creative culture through the years it is difficult now to get around it.

So what do we make of such contradictions in the history of beauty? Can we still make something beautiful without cynicism, cliché or sentimentality? Can we still admire a painting for beauty while also recognising abuse of power?

I, for one, believe we can. Imagine a philosophy of beauty that nurtures human imagination, cultivates creativity, causes humans to flourish, celebrates diversity, sets hearts on fire and souls to stir, yet also allows for the tension of disagreement. This, to me, would be truly beautiful.